Plastic waste poses a pressing problem for our planet's ecosystem, and especially our waters. Millions of tons of plastic waste enter the Earth's oceans each year, and plastic is found in every part of the ocean, including at the bottom of the deepest trenches. Although some biodegradable plastics or bioplastics have recently been developed, these plastics break down in industrial composting facilities. In the cold, dark ocean environment, they break down very slowly.

What if there was a way to avoid the problem of plastic pollution while still reaping the benefits of plastic's durability, versatility and low cost?

To solve this problem, a team formed by Anne Meyer, associate professor of biology at the University of Rochester, and Alison Santoro, a marine microbiologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, are working together to develop bioplastic, an environmentally friendly plastic material that can degrade in the marine environment.

Meyer and her lab were recently awarded $1 million in National Science Foundation grants that will create, for the first time, bioplastics that can degrade in the marine environment."

To make their marine degradable plastic, the team drew on processes already found in nature. Their material is based on a biopolymer called polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB), a type of polyester made naturally by bacteria. Because bacteria have been making this polymer for billions of years, other marine microbes have naturally evolved to break down PHB.

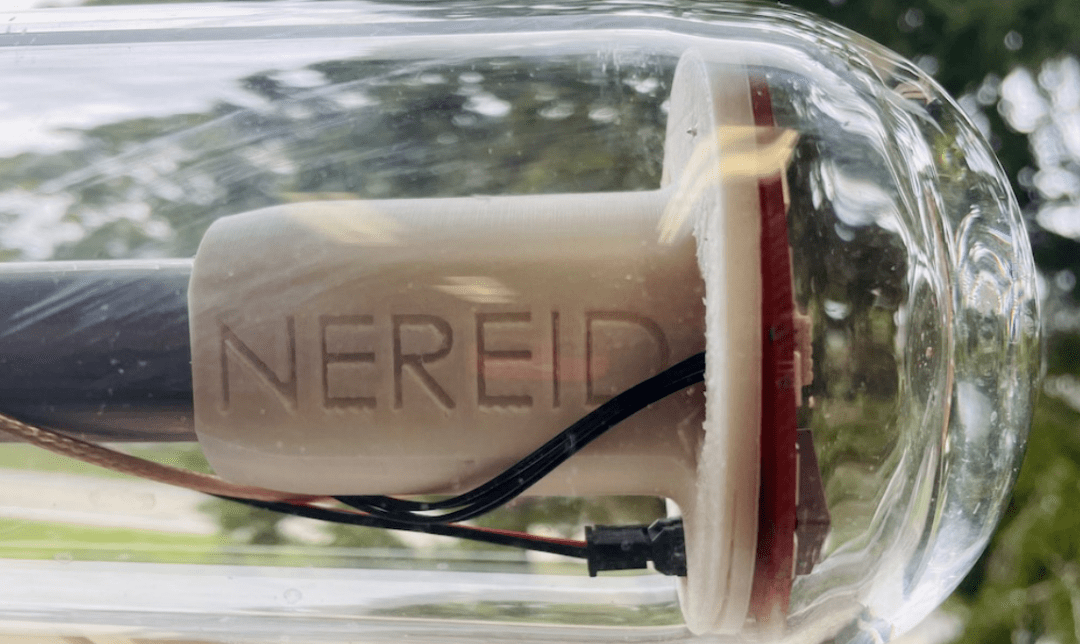

This is the first ocean instrument made from 3D printed internal parts composed of bioplastic. The instrument will be replicated and deployed in bulk to enable distributed measurements of the ocean carbon cycle.

The team used a revolutionary 3D bioprinting method to create a prototype of a marine degradable instrument. So far, the team has worked with five marine equipment manufacturers who have committed to replacing all or most of their traditional petrochemical plastic components with the team's marine biodegradable materials.

At the University of California, Santa Barbara, Santoro and her lab partners have cultivated a new bacterium capable of breaking down PHB.

One focus of their work was to isolate bacteria that thrive in the cold conditions of the ocean. They "fed" the microbes with methane from wastewater treatment plants, "which is another victory," Santoro said. "We see a huge demand for biodegradable materials, and users need items with a range of lifetimes," she added. The team talked to regulatory agencies and nonprofits that deal with marine debris and found that some groups wanted a material that could disappear in a day, others wanted equipment that would last a year, and still others wanted to trigger degradation.

That's where Meyer's lab comes in. Meyer and members of her lab have developed the first bacterial 3D printer.

This revolutionary 3D bioprinting method allowed them to create engineered living bacterial cells incorporating PHB-degrading bacteria.

The researchers' 3D printed living materials degrade the bioplastic structures around them. Strategically placing these bacteria in or on plastic provides the user with a choice of timing and speed of biopolymer degradation.