Because of the fear of marine life accidentally eating garbage to cause ecological crisis, how to deal with the "Pacific garbage belt", in the past years are many scholars research topics. However, a new study in Nature Communications found that a variety of coastal species have begun to settle in this new plastic habitat.

The situation is like the classic line from Jurassic Park, "Life will find its own way out.

Linsey Haram, a marine ecologist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), noted that the issue of marine plastic litter is not only about biological intake and entanglement, but that the litter also creates habitat opportunities for coastal species that go beyond what we previously thought was possible.

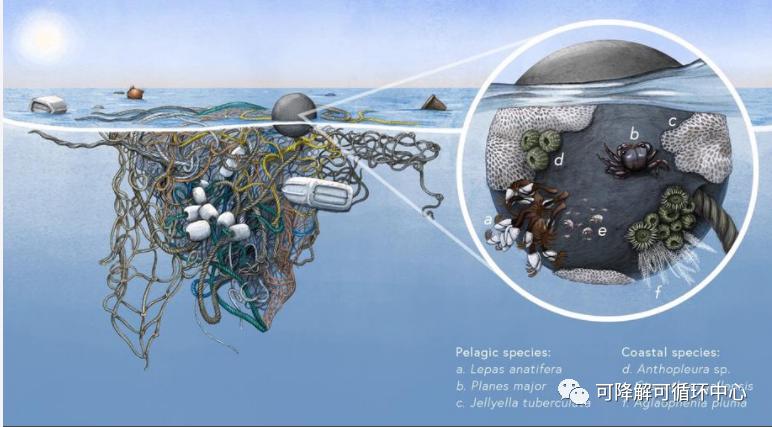

The coastal podshell hydroid Aglaophenia pluma, the pelagic small crab, and the pelagic gooseneck barnacle all live in the same patch of plastic.

The team called the habitat of these garbage belt organisms as "neopelagic communities". After the 2011 tsunami in Japan, scholars have begun to suspect that coastal species can use plastic to survive in the open ocean for long periods of time, and some teams have found that nearly 300 species have drifted into the Pacific Ocean on debris caused by the tsunami over several years, but finding coastal species directly on plastic in the open ocean was almost unheard of until the Haram team's observations.

The Haram team inventoried the marine species that call the Pacific garbage belt home to 79,000 tons of plastic trash and found that many coastal species including sea anemones, hydroids and shrimp-like telopods have not only survived marine plastic trash, but are thriving, living alongside pelagic native species.

SERC senior scientist Greg Ruiz pointed out that the open ocean has been considered uninhabitable for coastal organisms in the past because of habitat limitations and a food desert, as the academic community assumed. However, the new findings suggest that these two hypotheses are not always true. Ruiz said the team is still speculating on how this happens: whether it's through the circulation that turns the garbage patch into a biologically productive hotspot, or whether it's because the plastic itself acts as a reef, attracting more food sources. However, the open ocean is home to many native species that also have the opportunity to settle on floating debris.

The arrival of new coastal organisms could disrupt marine ecosystems that have remained undisturbed for thousands of years. Haram notes that coastal species are directly competing with these native species for space and other resources, and that scholars know little about their interactions. The team does not yet know how widespread these new pelagic communities are, whether the organisms among them are self-sufficient, or whether they even exist outside the North Pacific subtropical circulation.