With most of the millions of tons of plastic waste flowing into the ocean each year broken down into tiny pieces by the forces of the ocean, many researchers have begun to study what this means for life on Earth. Korean scientists have turned their attention to the top of the food chain to explore the threat these particles pose to mammalian brains.

Recently, several Korean scientists published a study titled "Microglia phagocytosis by polystyrene microplastics leads to immune alterations and apoptosis in vitro and in vivo," which showed that polystyrene microplastics (PS-MP) have a potential risk in microglia immune activation, which leads to microglia apoptosis in mouse and human brain. Apoptosis.

Although the effects of microplastics on the brain and behavior of aquatic animals have been reported in recent years, we still do not know how microplastics affect the brains of terrestrial animals and their underlying cellular physiology.

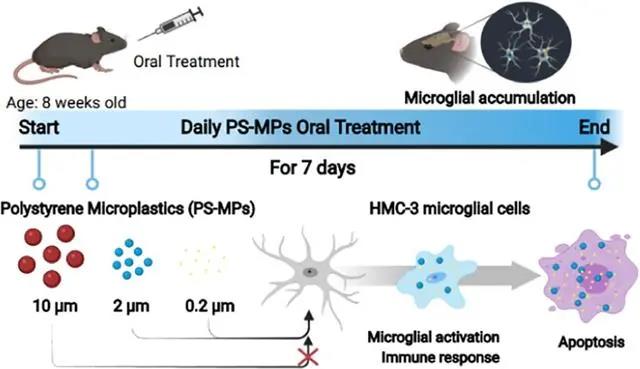

To learn more about these dangers, researchers at the Gyeongbuk Institute of Science and Technology in Daegu gave experimental mice oral doses of polystyrene microplastics 2 microns or smaller over a seven-day period. Like humans, mice have a blood-brain barrier that prevents most foreign substances, especially solids, from entering their organs, but the scientists were horrified to discover - the blood-brain barrier did not successfully intercept the microplastics.

Once the microplastics had successfully penetrated the blood-brain barrier, the last line of defense, and entered the brain, scientists found that these microplastic particles accumulated in microglia. Whereas microglia are key to maintaining the health of the CNS, the invasion of microplastic cells has a major impact on their proliferative capacity. This is because microglia perceive plastic particles as a threat, leading to changes in their morphology and ultimately to apoptosis or programmed cell death.

In addition, the scientists experimented with human microglia and also observed changes in their morphology, as well as changes in the immune system by altering the expression of related genes, associated antibodies and microRNAs. As seen in mouse brains, this also induced signs of apoptosis.

"The study shows that microplastics, especially those 2 microns or smaller, begin to deposit in the brain even after short-term ingestion over a 7-day period, leading to apoptosis, as well as altered immune responses and inflammatory responses," said study author Seong-Kyoon Choi, Ph. Based on the results of this study, we plan to conduct additional studies to further reveal the brain accumulation and neurotoxic mechanisms of microplastics."