Recently, the International POPs Elimination Network (IPEN) (hereinafter referred to as IPEN) published a series of studies that reveal the difficulties countries encounter in achieving a safe plastics recycling economy. Studies show that countries cannot safely deal with the constant and diverse flow of plastic waste. Moreover, due to the lack of laws and regulations requiring the labeling of plastic ingredients, chemicals that have been proven to be toxic are flowing unhindered into the markets of various countries.

According to IPEN, the production and use of plastics and chemicals is predicted to grow rapidly, which will only make these problems worse. It calls on countries to develop public policies to stop recycling the harmful chemicals in plastics that poison the circular economy and threaten human health.

IPEN also says that plastic manufacturers are the source of plastic materials containing toxic chemicals and should therefore be held financially responsible for all consequences arising during the plastic life cycle.

Toxic Plastic Waste in China, Indonesia and Russia

In order to clarify the risks associated with plastics and the circular economy, IPEN conducted a survey of three key economies: China, Indonesia and Russia. IPEN's analysis includes volumes and trends in plastics production, imports and use, as well as waste management, recycling and treatment systems. The results show that all three countries have adopted a series of measures with a view to achieving the safe management of large amounts of plastic waste.

For example, in China, there are two main systems for recycling domestic waste: the recycling system and the urban domestic waste collection and transportation system. All along, the two systems have been working side by side. However, urban household waste is increasing year by year, and the pressure on waste disposal is getting bigger and bigger.

In recent years, China has worked to strengthen the interface between the municipal solid waste sorting and recycling system and the renewable energy recycling system. Many cities have begun to take action: docking the recycling industry chain with the city's household waste network to improve resource utilization and reduce the burden of municipal waste disposal. This approach has been quite effective.

However, there are still many problems in this. The first and foremost problem is the presence of toxic chemicals in recycled plastics. IPEN conducted three studies on toxic chemicals in plastic and synthetic textile consumer products on the market (these chemicals are present to enhance the functionality of products such as stain and water resistance, or because of recycling of plastic products that already contain toxic additives). The three studies focused on the following chemicals commonly considered to be of concern.

Brominated flame retardants (BFRs) in recycled plastic products in China, Indonesia and Russia

Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) known as "permanent chemicals" in clothing in China, Indonesia and Russia.

Bisphenol A (BPA) in baby bottles in Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Russia, Sri Lanka and Tanzania.

Studies have shown that when people recycle plastic waste, these toxic chemicals, long banned under international chemical conventions, are transferred from old waste to new consumer products without knowledge of the ingredients, thus raising risks that are difficult to quantify. In addition, although toxic chemicals have been found to be hazardous and their use restricted or banned in other regions, they are still available for the production of consumer products in the countries assessed, further increasing the global supply of non-recyclable hazardous plastic waste.

For example, 73 samples analyzed from China, Indonesia and Russia were found to contain brominated flame retardants banned by the Stockholm Convention. The different compositions and levels of brominated flame retardants in the samples indicate that plastic waste of varying origins is used to produce recycled plastic, which is then used to make products such as toys, hair accessories, office supplies, and kitchen utensils. China, Indonesia, and Russia have not legislated to ban all brominated flame retardant POPs and all produce and receive e-waste containing these substances.

There are exemptions to the ban on some brominated flame retardants due to problems with recycling, and the concentration limits for POPs in waste under the Stockholm and Basel conventions are not stringent enough. This allows brominated flame retardants to be recycled and incorporated into new products, and end-of-life products and waste containing such contaminants to be exported to developing countries.

Vito Buonsante, IPEN's policy and technical advisor, said, "Overall, the findings paint a nightmare scenario in which countries are unable to deal with the complex and constant flow of hazardous waste, leaving the population with toxic chemicals in everyday products that they come in contact with on a regular basis."

Olga Speranskaya, an Eco-Accord policy advisor who participated in the study, said, "The results of our tests are concerning: toxic chemicals are widely found in children's products and other plastic consumer products. In addition, plastics contaminated with toxic chemicals are recycled into new products that frail people, including infants and pregnant women, are exposed to."

Yuyun Ismawati, co-founder of the Nexus3 Foundation in Indonesia, said, "We were surprised to find that every plastic product from China, Indonesia and Russia contained banned flame retardants. There is no government mechanism in place to warn people of the risks if they are exposed to these chemicals. It is clear that plastics are poisoning the circular economy."

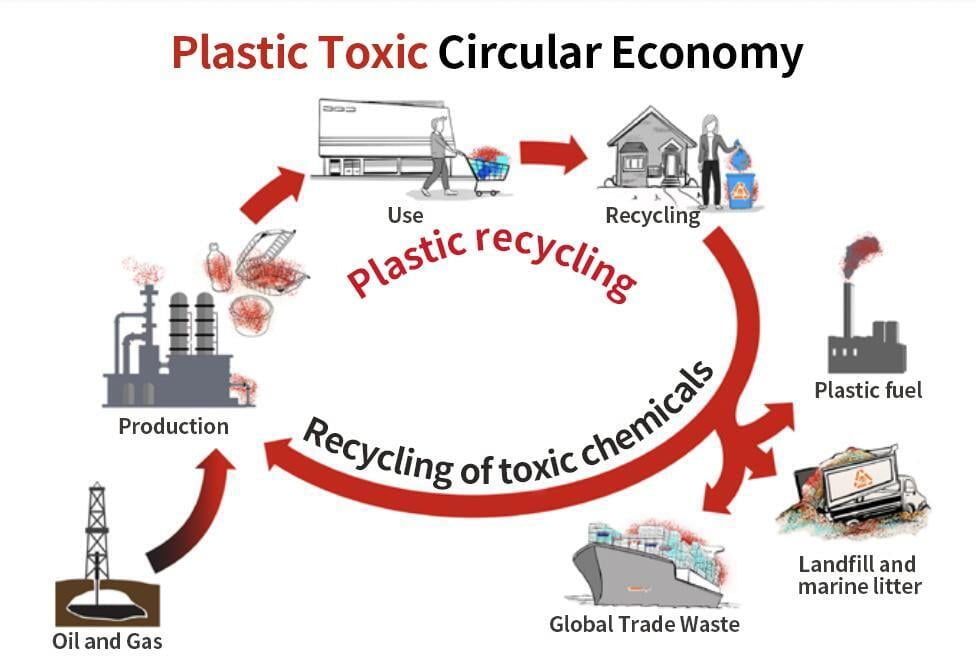

IPEN report "Plastic Toxic Circular Economy" diagram

Global guidelines need to be able to address multiple issues to be meaningful

IPEN believes that the international community needs to respond to the status quo as soon as possible. IPEN calls for.

1. Strengthen global policies to narrow the scope of commercial plastics and reduce the amount used, focus on the primary uses of plastics, vigorously remove toxic chemicals from virgin plastics, and strengthen chemical composition labeling.

2. Develop policies to protect human health and the natural environment to end hazardous plastic waste management. Specifically, prohibit the recycling of toxic substances, the use of plastic waste as fuel, and the disposal of plastic waste by incineration.

3. Hold plastics and chemical manufacturers financially responsible for the social, economic and environmental harms caused by their products through taxes, related fees and deposit rebate programs.